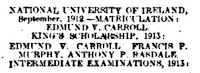

The small, slightly-built young man was speaking from the podium with deep, personal passion, appealing for votes from his own people. Frank Carney was addressing a room full of workers gathered to listen to the candidates for the election to the Enniskillen Urban District Council on January 9th 1920. Usually less than exciting, these Local Elections were important in Ireland in that they provided a barometer of Irish people’s support for Sinn Féin and for the continuing War of Independence. It also gave 22 year old Frank Carney the platform to launch himself on his political career, though surprisingly he did not stand as a Sinn Féin delegate.

This was the first Local Elections since 1914, and Sinn Féin

were fighting them with a total determination

to win, as they did in the national election of 1918. This was true in most of Ireland, with the exception, of course, of the northern counties where politics was a much more complex affair. The

election for the Enniskillen Urban District Council held on January 15th is a typical example, and

here no Sinn Féin candidates stood at all.

This was the first Local Elections since 1914, and Sinn Féin

were fighting them with a total determination

to win, as they did in the national election of 1918. This was true in most of Ireland, with the exception, of course, of the northern counties where politics was a much more complex affair. The

election for the Enniskillen Urban District Council held on January 15th is a typical example, and

here no Sinn Féin candidates stood at all.

Fermanagh had a majority Catholic population, and the Urban

District Council in Enniskillen had held a Nationalist majority since 1914.

These Nationalists were standing again, and they were from the old school of the Irish Parlimentary

Party and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. It is obvious that a deal was struck

so that no Sinn Féin candidates would stand against the Nationalists here, but candidates would be allowed to stand under the Labour Party banner.

There were four Labour candidates, and Frank Carney was one of these.

The Labour Party in Ireland was also a nationalist party, committed to Irish independence. It had emerged from the Irish Transport and General Workers Union in 1912 under the leadership of James Connolly and Jim Larkin. They also had a small militant wing in their union, the Irish Citizens Army, which was formed in 1913 to protect demonstrating workers.

As preparations for the Rising were being made by the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1916, James Connolly was brought into their confidence. Connolly was then appointed Commandant of the Dublin Brigade, de facto Commander-in-Chief of the Rising. Connolly's leadership in the Easter Rising was considered formidable. Michael Collins said of James Connolly that he "would have followed him through hell.”

|

| James Connolly's Execution |

|

| National Library of Ireland |

Frank Carney’s Speech - Fermanagh Herald Jan 10 1920

I have the honour of being

selected as one of the Labour candidates at the forthcoming municipal

elections. You would ask, quite naturally, what is our policy? Our policy is

Labour.

|

| Frank Carney |

Labour in this town has made its

demands very moderately, in a milk and watery sort of way, but we have got our

shoulder to the wheel and we mean to keep it to the wheel until Labour comes

out on top.

Our object in trying to get

representatives of Labour on the Urban Council is this: In the past Enniskillen

was run by a lot of traders from God knows where. The majority of them did not

belong to this town. What had been done by these civic fathers, the

capitalists, for the town of Enniskillen, for the working man?

|

| Forthill Enniskillen, started in 1845 |

They had got them the Forthill.

The working man’s wife could send a nurse up the Forthill to give the kiddies

an airing. What else had they got? They had got a concrete sidepath in the Brook for the elite to walk on.

The city fathers had promoted

lectures on the dangers of tuberculosis, but what did the workers get to

prevent their children from developing tuberculosis? Did they get anything more

in wages to enable them to by milk to build up the constitutions of the

children, or boots for them when they were going to school, or warm clothing? We

know ourselves the miserable starvation wages they had been in receipt of and

were in receipt of yet.

The civic fathers promoted

lectures on domestic economy and hygiene. We all know that the wives of the

working man are the only experts in this community on domestic economy, and

why? Because they themselves, their mothers and their grandmothers had been

educated in the science of domestic economy from the cradle to the grave. They

had to be economists or they would have died the week after they were married

owing to the starvation wages their husbands were receiving.

The civic fathers promoted

lectures on domestic economy and hygiene. We all know that the wives of the

working man are the only experts in this community on domestic economy, and

why? Because they themselves, their mothers and their grandmothers had been

educated in the science of domestic economy from the cradle to the grave. They

had to be economists or they would have died the week after they were married

owing to the starvation wages their husbands were receiving.

What did the workers get in the

way of sanitation in Enniskillen? Look at the Back Streets. What had they got

there? There are prehistoric institutions there and such conditions might be all

right in a Kaffir kraal, but they were absolutely abominable in a town like

Enniskillen.

The Labour candidates would be

asked what did they know about Enniskillen, but what did some of these city

fathers know about Enniskillen? Some of these traders walk about the town with

their fat cigars and expected the working men to bow and scrape to them. The

workers are now going to have a say in management of the town or know the

reason why.

If Labour candidates were not returned it would be the workers’ own fault.

Frank Carney January 19th 1920

If Labour candidates were not returned it would be the workers’ own fault.

Frank Carney January 19th 1920

___________________________